Secrets, Wisdom and Virtues Hidden in Basmala

In his renowned commentary, Ruh al-Bayan, the 17th-century Ottoman scholar Ismail Haqqi Bursevi highlights the profound significance of the Basmala—commonly referred to as the key to the Quran. According to a widely accepted view among later (müteahhirîn) Hanafi scholars, Basmala serves as an independent verse (âyah) that separates each surah, underscoring its role as a spiritual and theological gateway.

- Secrets, Wisdom and Virtues Hidden in Basmala

- Basmala in the Quran and Its Virtues

- Beginning Any Task with Basmala

- The Secret Within the Letter “B”

- Basmala and the “Ism al-Aʿzam” (Greatest Name)

- The Mysteries of Al-Raḥmān and Al-Raḥīm in the Basmala

- The Three Thousand Divine Names and Their Link to the Basmala

- References

Basmala in the Quran and Its Virtues

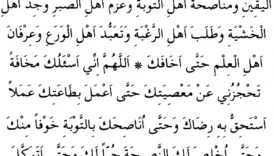

The Basmala:

بِسْمِ اللّٰهِ الرَّحْمٰنِ الرَّحِيمِ

Bismillāhir Raḥmānir Raḥīm

“In the name of Allah, The Most Merciful, The Especially Merciful”

This statement directs our prayers and intentions to the Divine, reminding us that genuine mercy, grace, and blessings all emanate from God. Ismail Haqqi Bursevi mentions that the Basmala was the very first phrase inscribed by the “Pen” in the Preserved Tablet (Lawh-i Mahfuz) and the first divine word revealed to Prophet Adam (peace be upon him). It is placed after the isti‘āẕa (seeking refuge with Allah) to symbolize that the heart must first be cleansed of distractions (takhliya) before it can be adorned with divine remembrance (taḥliya).

Beginning Any Task with Basmala

During the era of ignorance (Jāhiliyyah), polytheists would utter “In the name of Lāt and ʿUzzā” before any undertaking. By contrast, believers proclaim the name of the One God at the onset of any significant deed. Thus, starting with the Basmala—“I begin with the name of Allah”—invokes divine blessing and underscores the unity of the Creator in all actions.

The Secret Within the Letter “B”

A number of scholars have emphasized the mystery rooted in the Basmala’s opening letter, “B” (bā). Far from being a mere symbol, it conveys humility and subtlety. Unlike the towering form of the letter “alif,” which can signify grandeur, bā is typographically more modest. Yet it carries a special “dot” beneath it—an emblem of spiritual honor. Sufi tradition cites a saying attributed to ʿAli ibn Abi Talib (may Allah be pleased with him), “I am the dot beneath the bā,” linking bā to the essence of Divine oneness and spiritual guidance.

Moreover, bā is grammatically a ḥarf-i jarr (a “governing” preposition in Arabic syntax) that exerts an effect on the words following it, another reason it is considered more “active” than alif. Scholars also note how it is phonetically pronounced before alif can even enter the conversation—yet alif, when pronounced alone, never includes bā. This phenomenon hints at the divine wisdom in launching the Quranic revelation with bā rather than alif.

Basmala and the “Ism al-Aʿzam” (Greatest Name)

One of the most frequently discussed mysteries among Muslims is the concept of “Ism al-Aʿzam,” or Allah’s Supreme Name. Many interpreters hold that “Allāh” itself is the Greatest Name, representing the all-encompassing reality of the Divine Essence. However, to see one’s supplications answered, it is critical to follow certain guidelines—such as consuming only permissible (ḥalāl) sustenance and nurturing sincerity (ikhlāṣ) in the heart. Otherwise, even reciting the loftiest of divine names may not yield the expected outcome.

Mueyyid al-Dīn Jandī, a notable spiritual commentator, states that the Greatest Name manifests as a hidden reality spanning the realms of meaning (maʿnā) and outward form (ṣūra). Its perfection resides in the station of divine oneness (Aḥadiyya), and in every era, it unfolds through the most elevated human exemplar—known as the kāmil human being (al-insān al-kāmil), the spiritual pole (quṭb al-aqṭāb) entrusted with carrying the divine trust.

The Mysteries of Al-Raḥmān and Al-Raḥīm in the Basmala

- Al-Raḥmān (الرَّحْمٰن)

Rooted in the concept of raḥma (mercy), implying a profound gentleness and compassion. In practice, Ar-Raḥmān signifies that Allah provides and sustains every being without exception, warding off calamities and disasters, irrespective of people’s good or bad deeds. - Al-Raḥīm (الرَّحِيم)

Also derived from raḥma, but with a subtle distinction. Ar-Raḥīm emphasizes closeness and protection, hinting at a mercy that becomes even more apparent when it is actively requested. It is said that while human beings may grow irritated when asked for favors, Allah becomes displeased when people do not turn to Him in need.

Prophetic narrations further illuminate that God’s mercy extends far beyond our imagination. According to a well-known ḥadīth, Allah’s mercy is divided into one hundred portions, only one of which is manifest in this world, while the remaining ninety-nine will be revealed in the hereafter (see: Bukhārī, Al-Adab; Muslim, Al-Tawba).

Sufi scholars, such as Shaykh Dāwūd al-Qaysarī, explain that Allah’s mercy (raḥma) is essentially one reality, though it branches into various categories—zātī (essential) and ṣifātī (attributive), each of which can be both general (ʿāmm) and specific (khāṣ). This produces “four types of mercy,” from which emerge countless shades of divine kindness.

The Three Thousand Divine Names and Their Link to the Basmala

Another intriguing tradition states that Allah, Most High, has 3,000 names:

- 1,000 known exclusively by the angels,

- 1,000 known exclusively by the prophets,

- 1,000 divided among the four revealed scriptures: 300 in the Torah, 300 in the Gospel, 300 in the Psalms, and 99 in the Qur’an,

- And 1 name reserved entirely to Himself.

All these 3,000 names—so the narration goes—are encapsulated in “Allāh, Ar-Raḥmān, Ar-Raḥīm.” By uttering the Basmala, one calls upon every divine name and attribute of the Almighty.

References

- Ismail Haqqi Bursevi, Ruh al-Bayan

- Bukhārī, Al-Adab

- Muslim, Al-Alfāẓ, Al-Tawba

- Tirmidhī, Al-Birr

- Mālik, Al-Muwaṭṭaʾ (Kitāb al-Kalām)

- Dārimī, Zakat

- Al-Sakhāwī, Al-Maqāṣid al-Ḥasana

- Al-ʿAjlūnī, Kashf al-Khafāʾ

- Shaykh Dāwūd al-Qaysarī, various treatises

Note: Much of the commentary here draws on classical exegesis (tafsīr) and sufi (ʿirfānī) interpretations, as exemplified by works like Ruh al-Bayan. For a deeper investigation into the authenticity of specific narrations and ḥadīths, consult recognized ḥadīth compendiums and authoritative scholarly commentaries.

Views: 4